Dr. Ralph Blair 1972

(PDF version available here)

For too long, it has been an unquestioned assumption that every American boy and girl does or should grow up to be heterosexual. Such an expectation has contributed to much of the suffering of those for whom sexual development is otherwise. This monograph series is dedicated to these people and their families in the hope that it will enlighten readers to a more realistic expectation and greater understanding and enjoyment of each other’s lives.

A review of the test literature was done in 1957 by Grygier. He reviewed self-descriptive inventories, drawing tests, and projective techniques and concluded that no exact measures of the direction of sexual orientation were available at the time. The following year, even in reviewing his own test (The Grygier Dynamic Personality Inventory) with reference to its application to homosexual studies, he was obliged to conclude that, whereas his neurotic male patients with homosexual histories showed what he called a more “feminine” pattern of interests and attitudes from that which he judged to be shown by the non-homosexual neurotic male controls, nonetheless, there was still a need for a psychological test that portrayed diagnostically sexual orientation as well as the strength of that orientation.

Six years later, van den Aardweg (1964) reviewed the literature on male homosexuality in psychological tests. His conclusion was that the Rorschach, The Draw-a-Person Test, MMPI sub-scales, The Szondi Test, the Zamansky Test, and the House-Tree-Person Test were all useless for the individual diagnosis of homosexuality in males. He did feel, however, that there seemed to be some promise in the TAT. In 1967, van den Aardweg reviewed ten research reports listing measurements of neuroticism and self-pity for homosexuals, convicts, college students, and others and concluded that the homosexuals could not be distinguished from the others in psychological testing.

Some of the tests which are reported in the literature seem at best to be a waste of time – for they are supposed to furnish data for conclusions which are already known in terms of definitions and do not add to the store of information on homosexuality. For example, Zamansky tested the following propositions and reported that his experiment clearly supported the first two but gave only qualified support to the third:

- Overt homosexual males, when compared to normal males, will spend a greater proportion of time looking at a picture of a man than at a picture of a woman. 2. Overt homosexual males, when compared to normal males, will manifest a greater attraction to men than to neutral (nonhuman) objects. 3. Overt homosexual males will manifest (by more frequent choice of neutral objects) a greater avoidance of women than will normal males.

Another example is the series of penile volume measurements conducted by Freund in Czechoslovakia. He has been subjecting both heterosexual and homosexual males to sixty pictures of nude men, women, and children. On the basis of continuous measurement of the volume of the genital organ from flaccid (“0”) at the moment when the picture is first exposed to seven seconds later, —when the penis may or may not be in some state of erection—Freund has been noting which objects stimulate whom and has been correlating this information with subject assignment to one of four categories. The categories are: “pedophiliac” (aroused by those children under thirteen years of age), “ephebophiliac” (aroused by those males between thirteen and seventeen years of age), “androphiliac” (aroused by those males between seventeen and eighteen years of age), and “normal” (aroused by any of the females). Similar studies have been carried out by McConaghy.

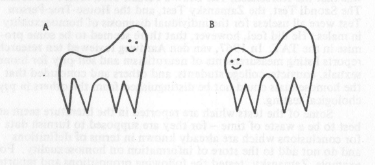

A third example of the tests which seem to be somewhat fruitless is also from Czechoslovakian research. Pinkava (Cited in Drum, 21, 1966, p. 9) claims that male homosexuals respond significantly more favorably to the figure “A” below than to the figure “B.”

Another example of a psychophysiological test is the pupillometric one developed at the University of Chicago by Hess and his associates. Hess’s procedure is to have his subjects peer into a box (The Pupil Response Apparatus) and look at pictures shown on a screen at the other end of the box. The subject’s pupil dilations and contractions are continuously photographed, enlarged twenty times, and measured to within l/20th of a millimeter. An increase in pupil diameter is taken to mean pleasure or interest in the picture whereas no increase is interpreted as disinterest or even boredom. Hess’s report, based upon his experiment with ten heterosexual males and five homosexual males who were each shown ten pictures including female and male nudes, is that the pupils of the heterosexuals enlarged whenever nude females were shown and that the pupils of the five homosexuals enlarged every time a male nude was shown. However, the pupils of one of the homosexuals also enlarged when female pictures were shown. Hess claims diagnostic reliability for his test, but Scott and his associates conducted experiments using Hess’s procedure and they could find no significant differences in interest by sexual orientation. They concluded that pupillary response is subject to much spontaneous variability which cannot be interpreted scientifically and that therefore use of the Hess test “in the diagnosis of individual interest patterns is not justified.”

Conflicting conclusions are also reported in vocabulary assessment techniques (Cf. e.g., Slater and Slater, 1947; Berdie, 1959; Clarke, 1965). Slater and Slater reported that their test, which consists of two sets of forty words each, one set of which is supposed to be known more to men than to women and the other set of which is supposed to be known more to women than to men, showed that homosexuals “knew many more feminine words than did the normal group.” However, Clarke points out that the two groups of subjects used by Slater and Slater were not systematically matched for age, I.Q., or social class. Correcting for these variables, Clarke concluded: “In the present study which controlled for these three variables their findings were not confirmed.”

Conflicting conclusions are reported with reference to the Szondi Test and homosexuality. According to David and Rabinowitz, the Szondi Test should not be used routinely in clinical practice. On the contrary, Bendel speaks of the Szondi Test as very useful for diagnostic purposes in male homosexuality.

The Draw-a-Person Test has also produced conflicting conclusions. On the one hand, Barker and her associates reported that ninety-two percent of their homosexual males drew a male figure first. On the other hand, Whitaker found that the tendency with his homosexual males was to draw a female figure first. Rizzo and his associates at the University of Rome could find no significant difference between heterosexuals and homosexuals on the Draw-a-Person Test with reference to the first figure drawn. Grams and Rinder reported that Machover signs for homosexuality in their administrations of the Draw-a-Person Test were neither individually nor collectively valid for prediction of sexual orientation. Hammer concluded also that “considerable doubt is cast on the projective drawing postulate that the sex of the first figure drawn may serve as an index of the subject’s sexual identification or as evidence of psychosexual conflicts of sexual inversion.”

Projective techniques such as the Rorschach and TAT have also produced conflicting conclusions with reference to their use with homosexuals. For example, Ferracuti and Rizzo found that the Rorschach differentiates homosexuals on an individual level but that the TAT does not do so. Coates claims that those patients of his who had had some heterosexual experience and whose Rorschach records indicated the “catastrophic” reaction to card II seemed to have a greater promise of “success in treatment.” Lindzey (1965) found that a clinician could blindly predict the criterion from TAT protocols with ninety-five percent accuracy and that twenty objective TAT indices, using actuarial methods after-the-fact, could predict as well as the clinician. However, when such actuarial methods were applied to a different sample of homosexuals, they were totally ineffective. Lindzey and his associates (1958) had found earlier that there was very good reason to doubt the utility of the TAT in homosexuality. Goldfried recently reviewed the literature on the use of the Rorschach in the diagnosis of homosexuality and concluded that there was very serious limitation in this regard. Carr and others examined the use of the TAT and Rorschach with homosexuality and found that no clear principles for predicting overt behavior were thereby to be had. This confirms the conclusions of Hooker with reference to the Rorschach. She gave the Rorschach to a group of thirty homosexuals whom she and her husband had met through social contacts in Los Angeles (a rare instance of the application of such tests to “normal” homosexual subjects) and to thirty heterosexuals matched for I.Q., age, and education. Her hypothesis was that homosexuality is not necessarily a symptom of pathology. The test results were analyzed by different, independent, and highly qualified judges who were not told whether a record was that of a homosexual or a heterosexual. The judges failed to distinguish homosexuals’ Rorschach records from heterosexuals’ records. Hooker thus concluded:

- Homosexuality as a clinical entity does not exist. Its forms are as varied as are those o f heterosexuality.

- Homosexuality may be a deviation in sexual pattern which is within the normal range, psychologically. This has been suggested, on a biological level, by Ford and Beach.

- The role of particular forms of sexual desire and expression in personality structure and development may be less important than has frequently been assumed. Even if one assumes that homosexuality represents a severe form of maladjustment to society in the sexual sector of behavior, this does not necessarily mean that the homosexual must be severely maladjusted in other sectors of his behavior. Or, if one assumes that homosexuality is a form of severe maladjustment internally, it may be that the disturbance is limited to the sexual sector alone.

The Blacky Test has been shown to be inadequate for the differentiating of overt male homosexuals from non-homosexuals. According to DeLuca, who administered the Blacky Test to twenty homosexuals and to forty non-homosexuals, the homosexuals showed a significantly greater disturbance on only one out of the thirty factors which were measured.

That alcoholism is a frequent factor in adult homosexuality has been left unconfirmed by the studies of Machover and his associates. They found that homosexual trends as scored on three tests were found no more frequently among male alcoholics than among non-alcoholics and non-homosexuals.

Conflicting reports are given for the MMPI. For example, according to Krippner’s study in which twenty students with homosexual problems and fifty-two students who did not present homosexual problems were subjects, the Panton and the Mf scales are reported to have correctly identified eighty and seventy-five percent of the homosexual subjects respectively. However, Dean and Richardson (1964), using the MMPI with forty college-educated overt male homosexuals and forty non-homosexual male college students produced results on four scales (Pd, Mf, Sc, and Ma) which could not be interpreted as being symptomatic of any general and severe personality disturbance. Nor could these scales show a significant difference between the two groups. In a later report, Dean and Richardson (1966) answered criticism of Zucker and Manosevitz that they had used a unidimensional framework instead of a multidimensional framework for differentiating homosexuals from heterosexuals. Dean (1967) developed a biographical questionnaire for information from homosexuals based upon paired categories and the MMPI.

Oliver and Mosher found a similarity between their psychotics and a group of homosexuals on the basis of the MMPI. However, their “homosexuals” were all reformatory inmates.

Feldman and MacCulloch administered the Eysenck Personality Inventory to a group of psychiatric patients who were diagnosed as homosexuals. These patients were found to be “more neurotic and less extraverted than the normals.”

Doidge and Holtzman have reported that in studying eighty homosexual patients and heterosexual non-patients at Lackland Air Force Base by giving them ten tests (The Sexual Identification Survey; Homosexual Homonyms; Edwards Personality Preference Schedule; Heineman’s Forced Choice Anxiety Scale; Worchel’s Self-Activities Inventory; Food Preference and Aversion Scale; Blacky Pictures Technique; Rorschach; MMPI; WA1S subtests—Vocabulary. Information, Similarities, Picture Completion, Block Design, and Digit Symbol), it was found that when the tests were scored by persons unaware of the sexual class of the subject in question, only the markedly homosexual group gave test records that were strikingly different from the control groups suggesting that markedly homosexual individuals are likely to be suffering from an emotional disorder which is relatively pervasive, severe, and disqualifying for military service.” This group, it must be noted however, was composed of men who had been gathered from the psychiatric ward on the base because they had presenting problems of homosexuality. Certainly these men were assumed to be “suffering from an emotional disorder” or they likely would not have been patients in the clinic. Doidge and Holtzman also report: “The partly homosexual group (composed of individuals who were predominantly heterosexual but with varying degrees of homosexual experience) gave test records that closely approximated the results of the two control groups” The researchers do not note their skew sample to homosexual patients, even though they acknowledge that “The almost complete lack of privacy in the barracks-type of living is likely to stimulate sexual drives in male homosexuals. Prevailing cultural attitudes and stringent military police heighten the conflict, precipitating contact with the psychiatric clinic.

Using as subjects one hundred adult male prisoners convicted of one or more homosexual offenses (another typical pool from which the researchers get their skewed samples of “homosexuals”) and comparing these with non-homosexual neurotics and with non-homosexual non-patient non-criminal subjects, Cattell and Morony interpreted the results of the administration of the “16 Personality Factor Questionnaire” on temperament and dynamic traits to mean that homosexuals are more neurotic than normals!

Such then, is a sample of the literature on psychometrics as related to homosexuality. As is evident, there is no real support here for the pathological theories. What “support is afforded must be understood in the light of the fact that when one uses, as test subjects, persons from psychiatric wards and prisons, one is not apt to end with “normal”—not to mention “fully-functioning”—persons. No test results indicate that it is possible with good reliability to differentiate in terms of sexual orientation where true matching of experimental and control subjects on all relevant variables except sexual orientation is observed.

References

Barker, A. J., et.al. “Drawing characteristics of male homosexuals,” Journal of Clinical Psychology, 9, 1953, pp. 185ff.

Bendel, R. “The modified Szondi test in male homosexuality,” International Journal of Sexology, 8, 1955, pp. 226f.

Berdie, R. F. “A feminine adjective check list,” Journal of Applied Psychology, 43, 5, 1959, pp. 327ff.

Carr, A. C., et.al. The Prediction o f Overt Behavior Through the Use of Projective Techniques. Springfield, Illinois: Charles C. Thomas, 1960.

Cattell, R. B. and Morony, J. H. “The use of the 16 PF in distinguishing homosexuals, normals, and general criminals,” Journal of Consulting Psychology, 26, 1962, pp. 531ff.

Clarke, R. V. G. “The Slater Selective Vocabulary Test and male homosexuality,” British Journal of Medical Psychology. 38, December 1965, pp. 339f.

Coates, S. “Homosexuality and the Rorschach Test,” British Journal of Medical Psychology, 35, 1962, pp. 177ff.

David, H. P. and Rabinowitz, W. “Szondi patterns in epileptic and homosexual males,” Journal of Consulting Psychology. 16, 1952. pp. 247ff.

Dean, R. B. and Richardson, H. “Analysis of MMPI profiles of forty college-educated overt male homosexuals,” Journal of Consulting Psychology, 28. 1964, pp. 483ff.

_________________________. “On MMPI highpoint codes of homosexual versus heterosexual males,” Journal of Consulting Psychology, 30,6, 1966, pp. 558ff.

Dean, R. B. “Some MMPI and biographical questionnaire correlates of non-institutionalized male homosexuals.” Master’s thesis. San Jose State College, 1967.

DeLuca, J. N. “Performance of overt male homosexuals and controls on the Blacky Test,” Journal of Clinical Psychology. 23. 1967, pp. 497.

Doidge, W. T. and Holtzman, W. “Implications of homosexuality among air force trainees,” Journal of Consulting Psychology, 24, 1960, pp. 9ff.

Feldman, M. P. and MacCulloch, M. J. Homosexual Behaviour: Therapy and Assessment. Oxford: Pergamon, 1971.

Ferracuti, F. and Rizzo, G. B. “Homosexuality signs in projective techniques in a female prison population,” Revista de Ciencias Sociales, 2,4, 1958, pp. 469ff.

Freund, K. “A laboratory method for diagnosing predominance of homo- and hetero-erotic interest in the male,” Behaviour Research and Therapy, 1, 1963, pp. 85ff.

______________. “Diagnosing homo- or heterosexuality and erotic age-preference by means of a psychophysiological test,” Behaviour Research and Therapy, 5, 1967, pp. 209ff.

Goldfried, M. R. “On the diagnosis of homosexuality from the Rorschach,” Journal of Consulting Psychology, 30, 1966, pp. 338ff.

Grams, A. and Rinder, L. “Signs of homosexuality in human-figure drawings,” Journal of Consulting Psychology, 22, 1958, p. 394.

Grygier, T. G. “Psychometric aspects of homosexuality,” Journal of Mental Science, 103, 1957, pp. 514ff.

______________. “Homosexuality, neurosis and ‘normality,’” British Journal of Delinquency, 9, 1958, pp. 59ff.

Hammer, E. F. “Relationship between diagnosis of psychosexual pathology and the sex of the first-drawn person,” Journal of Clinical Psychology, 10, 2, 1954, pp. 168ff.

Hess, E. H., et. al. “Pupil response of hetero- and homosexual males to pictures of men and women,” Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 70,1965,p p .165.

Hooker, E. “The adjustment of the male homosexual,” Journal of Projective Techniques and Personality Assessment, 21, 1957, pp. 18ff.

___________________. “Male homosexuality in the Rorschach,” Journal of Projective Techniques and Personality Assessment, 22, 1958, pp. 33ff.

___________________. “The adjustment of the male overt homosexual,” in Ruitenbeek, H. M. (ed.) The Problem of Homosexuality in Modern Society. New York: E. P. Dutton, 1963.

Krippner, S. “The identification of male homosexuality with the MMPI,” Journal of Clinical Psychology, 20, 1964, pp. 159ff.

Lindzey, G., et. al. “Thematic Apperception Test: An empirical examination of some indices of homosexuality,” Journal of Abnormal Social Psychology, 57, 1958, pp. 67ff.

Machover, S., et. al. “Clinical and objective studies of personality variables in alcoholism,” Quarterly Journal of Studies on Alcoholism, 20, 1959, pp. 528ff.

McConaghy, N. “Penile volume change to moving pictures of male and female nudes in heterosexual and homosexual males,” Behaviour Research and Therapy, 5,1, 1967, pp. 43ff.

Oliver, W. A. and Mosher, D. L. “Psychopathology and guilt in heterosexual and subgroups of homosexual reformatory inmates,” Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 73, 1968, pp. 323ff.

Panton, J. H. “A new MMPI scale for the identification of homosexuality,” Journal of Clinical Psychology, 16, 1, 1960, pp. 17ff.

Slater, E. and Slater, P. “A study in the assessment of homosexual traits,” British Journal of Medical Psychology, 21,1947, pp. 61ff.

Scott, T. R. et.al. “Pupillary response and sexual interest reexamined,” Journal of Clinical Psychology, 23, 1967, pp. 433ff.

van den Aardweg, G. J. M. “Mannelijke homosexualiteit en psychologische tests,” Nederlands Tijdschrift voor de Psychologie, 19, 1964, pp. 79ff.

___________________ . “Homofilie en klachtenlijsten: Een overzicht van de gegevens,” Nederlands Tijdschrift voor de Psychologie en haar Grensqebieden, 22, 1967, pp. 687ff.

Whitaker, L. “The use of an extended draw-a-person test to identify homosexual and effeminate men,” Journal of Consulting Psychology, 25, 1961, pp. 482ff.

Zamansky, H. S. “A technique for assessing homosexual tendencies,” Journal of Personality, 24, 1956, pp. 436ff.

Zucker, R. A. and Manosevitz, M. “MMPI patterns of overt male homosexuals,” Journal of Consulting Psychology, 30, 6, 1966, pp. 555ff.